Chapter 1

A sign of the times was encased in metal and placed on the front desk when the children of a town called Azier filed in for their first history class of the school year. Faenon’s father once had a lamp just like it. It now lay with the clutter in the old barn after either Faenon or his brother knocked it over and shattered the glass. Although the style of this lamp was more ornate, Faenon recognized it at once by the flame that flickered with no wick or fuel.

A man with a grin more oily than his hair watched proudly while his students gawked at the device from no nearer than two feet away. When the classroom had filled, he held the lamp, which he called an elven light, close to his face to demonstrate its glow in the daylight coming through the dusty windows. With the flick of a switch, the man turned it off, then on again, to audible gasps.

“I thought I’d start the first day of our Human-Elven Relations class by sharing this new technology with you,” said the man. His name was written in chalk behind him, but Faenon could not read the looping cursive from the back of the classroom. “The elven light is a beautiful symbol for what humans and elves can accomplish when we work together.”

“Can you pass it around?” asked a voice next to Faenon that belonged to one of the few elves living in Azier. There were only three that he knew, all students, and all bearing the family name Itona. The two girls were twins aged eleven, and one was never without the other. They had identical rosy faces and always dressed in the style of rich city ladies, but could be differentiated by the color that crept into their fine, white hair. One had pale streaks of blue, while the other had tips of violet. The only reason anyone confused one for the other was because their names were Zuli and Yuli, and no one could remember which twin was which.

The teacher’s smile faltered for only an instant, after which it seemed even falser. He reluctantly handed the elven light to someone in the first row. As he talked about his personal background in the brief history of elves and humans, he gripped the edge of his desk and leered at the students mishandling his lamp.

He hardly had to tell the students he was born in Azier and had studied in Meryville. He had the haughty air of a Gardenian, as did all who lived too long in the capital city of Gardena, especially those who went to the Meryville University. As for his heritage, the only men who would dare come to Azier from the direction of Gardena were Azierites themselves, or fools. Azier was a village surrounded by stone walls, watched by guards, and filled to the brim with warriors eager to kill, or so went the stories.

Most of the children in the classroom barely touched the elven light when it came to their seat, as if afraid. It arrived at last at Faenon's desk with the whisper, “It smells like blood.”

The scent told him that the lamp was cast in iron. The iridescence of the mounted stone, casting the floating flame, told him that this power was never meant to be used as a trivial appliance. The lingering chill in his fingertips after he passed the light to his left told him something he already knew, but still could not articulate, about Gardena.

“We’re going to start today’s lesson at the very beginning,” the teacher said. “It’s been… what, almost fourteen years, hasn’t it? Are any of you old enough to remember the Celestial Event?”

Faenon alone raised his hand. At seventeen years old, he was among the dwindling few in the oldest class at Azier’s school. If not for his father, he would never have stayed so long, not when most of his peers had left school to follow their parents into trades or to take their weapons training to the Northern Army. Though bright, motivated, and a quick learner, Faenon had never liked school. He could not tolerate the artificial power dynamic between student and teacher. The only reason he had even seen the Celestial Event was because he had disobeyed the teacher herding children into the school’s basement. The whole town streamed into cellars and crawlspaces to hide from whatever had made the sky start to scream out in agony unlike any storm known to man. The whole town, but for two children.

“Oh, so we’ve got one!” said the teacher, brimming with energy. “I might ask you a few questions about it, if you don’t mind. What’s your name?”

“Faenon. Faenon Winter,” he replied, watching his teacher’s face fall.

Faenon looked like a nice enough boy if one did not notice his smug grin and the glint of mischief in his big, brown eyes. He had a youthful face for seventeen years: a strong but hairless jawline under round cheeks, framed by unkempt curls of dirty blonde, with a bit of a snub nose. He never had a height advantage, but discipline with his great battle axe gave him the strength he needed to stand tall no matter whom he faced. By the time he reached his preteen years, he noticed that new teachers cringed when they heard his name, presumably because they had been warned.

“Faenon,” repeated this new teacher with disgust. “Well, did you want to share anything about your experience?”

Faenon beamed with his signature grin and shrugged. “I don’t care,” he said. “You probably remember it better than I do.”

“Fair enough,” he responded on a sigh, perhaps one of relief.

He launched back into his lesson as swiftly as possible by recounting what little the University’s best scientists knew about the Celestial Event. Faenon might have paid attention if the University’s best scientists could explain any more than what the general public already knew: over the course of a strange day, a whole world’s worth of human-shaped people began falling to the earth from holes in the sky. Even the highest scholars in the world still did not know from where they came, or why, or how.

Faenon’s wandering mind picked up on the thread of the whispered conversation next to him. He found he could not let it go.

“It feels unstable. It’s not cleaved,” said the Itona twin to his immediate left, the violet-haired one. “Stupid cheap Gardenian knockoffs. It’s always a knockoff when they call it an elven light, not a Highland light, y’know?”

She and her sister huddled at her desk, examining the lamp. “What do we do?” said the blue-haired one. “He’s watching us. We can’t just take it apart right here and—”

“Yeah, you can, Yuli,” said the purple twin, with an audible eyeroll in her tone. She passed the lamp over and scooted her desk a few inches closer. “We’ll cover you. Raz has gotta be listening.”

Not a moment later, the third and final elf in Azier waved his dainty hand in the air. “Excuse me, I have a question!”

Usually, when Faenon disagreed with or even disliked one of his peers, he enjoyed fights with them, whether verbal or physical, to prove his side right. Raz was the exception to this trend. Faenon could not think of a peer he hated more than Raz, but Raz could not fight, and conversations with him were downright uncomfortable.

“Yes?” the teacher answered with disdain, not only because of the abrupt interruption, but also because Raz had an appearance that invited disdain. Though his cousins Zuli and Yuli also had unusually colored hair, his beat theirs out with a bright shade of bubblegum pink, which he attested was, like theirs, completely natural. As if that were not garish enough, he favored a patchwork jacket of heavily pigmented cotton squares in too many contrasting colors. He sat in the front of the classroom with an upright spine, his legs crossed at the ankle, and his hands resting gently on the fine, smooth paper of his notebook, next to which he placed his small bottle of ink and his black feather quill. Every other student in the school used charcoal or graphite pencils.

“Pardon me for the interruption, sir,” Raz said, “but where did the word elf come from?”

Faenon caught movement in the left corner of his eye. The blue-haired twin—evidently this one was Yuli—held her hands near the elven light on her desk, not moving or touching it, but the bolts securing the glass were coming undone of their own accord. Her sister Zuli rolled her eyes again before hissing, “Faster.”

“In our language, we call ourselves isinni,” Raz continued in his loud and musical voice, “but when we came here, everyone started calling us elves and I have no clue why and neither does anyone else I’ve ever asked.”

The entire class, the teacher included, was stunned into silence by the question. Faenon flicked his eyes to the left when a small clink of glass was exposed in the stillness. Panic filled Yuli’s eyes as she held the glass casing of the elven light, suspended in the air with her magic, separate from the base.

“Wait, you don’t know?” Faenon asked, frowning.

The teacher’s stance shifted inward in the blink of an eye. It was a deferral of authority, and more importantly to the twins, a high-stakes diversion.

“I can’t say I’ve ever come across that in my research,” he said, beginning to mumble.

“How the—I even know this one.” Faenon swung his legs up to the surface of his desk. “It’s from old fairy tales. It’s a—it was supposed to be a made-up race. They said they kind of look like humans but with pointed ears. Don’t know how it caught on, but it’s obvious where it came from.”

In his peripheral vision, he saw more than a few impressed nods for his explanation of events. He kept his eyes locked on the teacher to leave a lasting memory of the first moment he took authority back away from the front of the classroom.

“That’s very insightful information. Thank you, Faenon,” said the teacher while gripping the edge of his desk and wearing what could only be called a smile by process of elimination. “Could I ask where you got that information so that I can verify it when I return to the University?”

Though he disguised it as genuine interest, it was a clear grab for the power he had lost. He stiffened his grammar and his vocabulary while delivering a reminder that he was the University scholar in the room, not Faenon.

“No need to head back to Gardena. We got the books in our library,” Faenon replied, thumbing over his shoulder despite having no frame of reference for where the library was. “The new curator’s read all of them. You and her could have a good chat about it.”

He glanced over at the Itona twins as he finished. The elven light was already reassembled, screws and all. Yuli held a sliver of stone between her thumb and forefinger. It was small, about the size of the part of the lamp’s inner stone that pulsed with a hot glow as if wounded. Yuli smiled at Raz, who had turned around in his chair to pretend to listen to Faenon.

“Is there something the matter with the light, ladies?” the teacher asked, frowning.

Yuli stuffed her hand into her pocket and sat up straight, shaking her head so fast that her chin-length hair hit her in the mouth with every turn. Zuli scooted her desk back into place, flashing a sweet smile that highlighted the plump, pink apples of her cheeks. “No, I just was trying to understand how it works, Mr. Eller,” she said.

“Well, that makes two of us,” chuckled the teacher. “It’s new technology beyond any of us.”

“Do you even know anything?” Zuli uttered through her smile as she passed the lamp onward.

“Is this a good time to ask another question, sir?” Raz interjected, resting his pointed chin on his thin, interlaced fingers. “Because I have a bit of a curriculum question, as well. I think we all have the same question, but we’re all too shy to ask about it. It’s a little touchy, you understand.”

Rune had specifically told Faenon not to stare at him every time something controversial came up in class, but Faenon could not stop himself. Rune sat just a little ways out of his line of sight, but the straight, red hair that he had not cut in over a year veiled what would have been a blank face, anyway. He protected himself by casting his face in stone, immutable and emotionless no matter what the teacher said next. Though he posed as Faenon’s brother, Rune was one of many children, but perhaps one of the few still alive, at the darkest heart of human-elven relations.

“So what’s the good Gardenian dirt on the half-elf genocide?” Raz asked, beaming stupidly from ear to pointed ear.

The sound was sucked out of the room. A student froze in the midst of walking to the front desk to return the elven light to Mr. Eller, who would have been too stunned to accept it in any case.

“I think,” Mr. Eller began with a nervous laugh, “that you’re getting the wrong impression of what’s going on in Gardena.”

“The impression we’re getting is that half-elves are being abducted by the government and their parents are being thrown in jail,” said Faenon. “You can maybe call that ‘not genocide’ if the next thing you say is ‘yet’.”

As expected, Rune faced forward with no shift in his expression or his posture. However, the edge of Faenon’s notebook was lighting with a small, green flame, so he knew that his brother was angry with him. Pulling his feet swiftly off of his desk and back to the floor, he smothered the fire with the callused part of his palm at the base of his fingers and resumed eye contact.

“That’s…” Mr. Eller held his mouth open, but words failed to come out of it for too long. “I can see how you might come away with that interpretation,” he said finally, folding his arms. “The order of events is a little off. The law criminalizes the knowing conception of a half-elf—it’s the fault of the parents, not the offspring, after all—and instead of just leaving the half-elf to die, the government takes it into custody.”

“It?” whispered Yuli to her sister, making a face.

“So that’s really what’s going on,” Mr. Eller said. “The Gardenian government is doing all it can to assist with the current crisis.”

“How is this a crisis?” Faenon demanded. “Who decided it was a crisis that humans and elves are getting married and having children? Why is that so wrong?”

“Listen, Faenon, I understand where you’re coming from, I really do,” said Mr. Eller with a patronizing smile, “but it’s much more complicated than you’re making it sound. It’s nuanced biological science that you wouldn’t understand, but I can try to simplify it for you after class if you’d like to hear about it.”

Faenon counted on his fingers the grievances he had with what Mr. Eller had just said, so that he would remember them all as he made his rebuttal.

“So you don’t know where the word ‘elf’ comes from, you don’t know how elven lights work, you don’t sound like you really knew why the Celestial Event happened any more than we already did,” Faenon said, “but it just so happens that you’re some kind of science expert who’s all prepared to tell us why half-elves are some kind of biological atrocity. Who sent you here and how much are they paying you to spread the propaganda?”

Mr. Eller’s face was stony. “This was the subject of my thesis at—”

“Second of all, don’t talk down to me,” Faenon continued in a louder voice. “You’re a teacher. Your job is to share your knowledge, not to brag about how much smarter you are than us. If I have a question, I deserve a decent answer. Third, don’t try to stop the conversation that’s happening here by telling me to talk to you after class. It’s a cold day in hell when I agree with Raz on anything, but we all want to know what’s going on in Gardena, so you’re going to tell us right now why your messed-up government hates half-elves.”

Though reviled by his teachers, Faenon won the admiration of his peers with his command of speech. When he made his opinion known, it echoed through the student body. He had been the first one to call the Gardenian laws an act of genocide, and now the whole school was using his word. Of course, he took the word, and all of his talents of rhetoric, from his father.

“The government does not hate half-elves,” Mr. Eller insisted, gripping both sides of his desk as he loomed over it, red with rage and embarrassment. “I didn’t want to oversimplify things because it’s such a delicate issue with a lot of complexities, but, if you’re forcing me to give you knowledge that you can understand, it’s because half-elves are born with defects.”

When Faenon shot back, “That’s a load of bull,” he nearly bit his tongue. He did not notice he had been standing until he fell back to his chair after realizing he had gone too far.

“That’s the result of over a decade of research done on the half-elves in government custody,” said Mr. Eller. “You come across as someone in the habit of shouting your opinions loudly enough that you don’t have to hear the facts proving you wrong. Is that true?”

Raz snapped his fingers and let out a soft “ooh” to send his compliments to the teacher, grinning wickedly. Faenon threw him a glare.

“Have you ever seen a half-elf, Faenon?” Mr. Eller asked.

“Have you?” he responded to avoid admitting anything.

“I’ve studied several in my time at the University. Seeing their defects firsthand was what inspired me to pursue my research,” said Mr. Eller. “There are incredibly detailed case studies on the first known half-elf, which was born missing an arm and had a weak heart—I think it died in infancy from the medical complications. And the half-elf I studied in Meryville was blind and incapable of speech—essentially, a mute.”

The word “mute” brought a grimace to Faenon’s face, and at the same time, Rune drew his arms closer to his body.

“In our studies we discovered that it also could not comprehend any spoken language we tried to teach it,” continued Mr. Eller. “You’re envisioning innocent children, Faenon, and they are innocent, but they aren’t like us. It’s tragic to see one in person.”

“You’re going to stop calling these kids ‘it’ right now,” Faenon growled, squeezing his eyes shut. “How do you know it’s because they’re half-elves? People are born blind and mute and sick and missing limbs all the time.” His eyes shot up when he remembered the name for the phenomenon he was describing. “Confirmation bias. You’re actively looking for reasons to prove your side right. It’s called confirmation bias.”

He had a rudimentary understanding of logical fallacies and cognitive biases, having learned many by name from conversations with his father. They still seemed to him a list of magical phrases that his father could say to render Faenon’s argument automatically invalid.

“I’m impressed you know about that, Faenon. But did you know we’ve developed mathematics to prove that there is no bias?” Mr. Eller replied. “There’s a higher rate of certain defects in half-elven populations. The current theory is it’s the biological incompatibility between humans and elves.”

Faenon lost his patience.

“What biological incompatibility? Who told you there was a biological incompatibility? The same government that’s trying to kill the half-elves?!” he shouted. “You wanna talk biology? Althea Rider says if you cut the ears off a guy, she couldn’t tell you if he was a human or an elf. That’s how similar they are.”

Mr. Eller’s nose wrinkled in disgust. “Now, listen, I’ve heard about Miss Rider, but she’s certainly not an authority on these—”

“Althea Rider is the only authority!” Faenon yelled as he slammed his hands on his desk and shot to his feet, boiling with fury. “Althea Rider is the first healer this world has seen in literally thousands of years! If you’re not going to listen to someone who can actually commune with people’s bodies—”

“I listen to facts, Faenon,” Mr. Eller stated. “We’ve conducted study after scientific study proving there’s something wrong. Half-elves are prone to certain psychotic disorders, to birth defects, as I already—”

“Psychotic? That’s mental stuff, right?” Faenon said. “So a whole bunch of kids you lock up in some secret facility away from the rest of society go insane? What a stunning revelation. Never would have guessed.”

“Alright, that’s not what’s happening,” said Mr. Eller, “but even if it were, I would love to hear an explanation for how isolation causes identity disorders.”

For a moment, Faenon was very far away from their conversation. His body became numb. “Identity disorders,” he finally repeated.

“I warned you this would get complicated,” Mr. Eller sighed. “It’s a psychotic disorder in which people believe they’re someone or something else—often it presents as a male believing he is female, but occasionally someone may believe they are an animal or even an inanimate object, or a character from a storybook. It’s far beyond the realm of make-believe. It’s a persistent delusion that manifests over the course of months or even years. We’ve never seen this many cases of these disorders in all of Meryville, and we’re only working with about a dozen half-elf subjects.”

Faenon had begun counting points of contention on his fingers, but he went past five, and he could not speak about any of them, so they combined into a hot rage in his arms and his face. He shuddered with a burst of hateful energy and shoved his desk to the floor, where it clattered loudly, startling the classmates who were not watching him and intriguing those who were.

Rune held his hands clasped together and rested his forehead on his fingers, concealing his face with his long, red hair. Faenon kept his eyes on his feet as he stomped towards the door.

“Is there a problem?” asked Mr. Eller with his oily grin. “I know it’s hard to hear the truth when you’ve denied it for so long, but you don’t have to leave.”

Faenon hated losing, and he knew that to leave now was an apparent loss, but Rune was begging him with white knuckles to leave it be. “I’m leaving so you can keep your teeth,” he seethed as he walked out the door. “I don’t know where to even begin with you.”

It was coming on fourteen years to the day since both the Celestial Event, and since Althea Rider discovered her healing magic. When an elven boy fell too far from a hole in the sky during the Event, she made the scrape on his elbow disappear with a sweep of her little hand. Despite how often she had talked of going to Meryville to study, or traveling across the continent to help those in need with her talents, or doing anything she possibly could to leave Azier and its people behind as soon as she became an adult, Althea had barely left school after graduating. She stayed to preside over the small building that had been like a second home throughout her childhood, and the one that Faenon still struggled to find after all these years: the library.

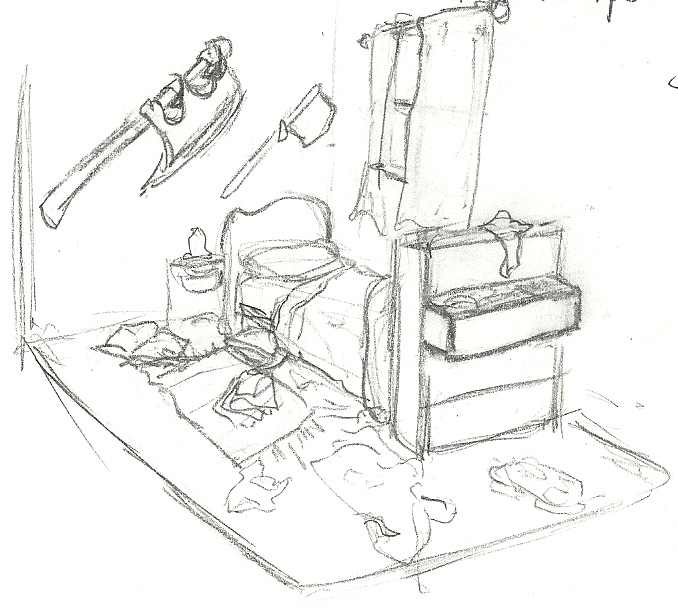

The cavernous room was dimly lit and smelled of mildew. When Faenon had blinked the sun from his eyes, he saw books lining the shelves in tragic disarray. A couple of shelves had had their contents removed and placed in sorted stacks on the ground, but it was a task abandoned. At the front desk sat a young woman lost in a slim volume. Since her early teens, she had taken to wearing a scarf, even in warm weather, to hide a thick neck and mask her broad shoulders. Her collected composure broke with a pronounced slouch when she saw Faenon peer in the door.

“Can I help you find something?” she asked. Her voice had depth and power, especially when it dripped with sarcasm. “Maybe your classroom? Your sense of respect?”

“Patience, maybe,” Faenon muttered.

“Shame. So you lost the first argument of the school year,” Althea sighed, picking up her book again. Before he could launch into an excuse, she snapped, “Suck it up and go back to class. I’m not going to be your stand-in punching bag.”

“I’m not going back to class. It’s worthless,” Faenon grumbled. “If you’re really going to go study in Meryville someday, promise you won’t come back and tell people there’s not a genocide.”

Althea lowered her book to the desk and folded it closed over her fingers, staring at the blank leather cover. “The Human-Elven Relations teacher?” she said. “They taught him to lie to you?”

“Could be. He sounds more rehearsed than the school choir.”

“The choir is terrible.”

“It was a multi-faceted joke.”

Althea lifted her book again, flipping it open to her marked page with a single-handed flourish. She shoved Faenon away from the desk with her other hand. “You can’t risk getting a detention today, can you?” she said. “Get moving.”

“You don’t automatically serve detention the day you get it,” Faenon groaned. “’Course you wouldn’t know that, you goody-two-shoes.”

“My after-school duties include supervising detention,” she said icily. “I’d be happy to make room in my schedule for you this afternoon, Faenon.”

“No, come on, hey,” he protested, gripping the edge of her desk. “Don’t—your dad said he’d—c’mon, he never does this anymore, you can’t—”

He glanced down when Althea slid her feet apart to strengthen her large stance. She had worn her mother’s army boots every day since they first fit on her feet. She had never had a problem with wearing flowing skirts, sheer and embroidered fabrics, and long hair—very, very long hair—unlike many of the rougher girls of Azier, but she would wear nothing else but those army boots for shoes. To her, they represented power that was strictly feminine.

“Then go back to class,” she commanded.

Faenon would talk back to his teachers, his coaches, and even his father when they tried to tell him what to do without giving a good reason. Althea was the only person who could still scare him into obedience. He watched her eyes for another few seconds, hoping for a change of heart. When he saw none, he trudged away from the desk and out of the library.

“He probably has a job you could do,” Althea called as Faenon opened the door. “I’ll count that as detention served if you do it without picking a fight.”

Faenon froze in the doorway, frowning, until he squinted into the sunlight to see Althea’s mystery person sauntering towards him, one slender hand in his pink hair, the other folded around a ream of papers.

“Well, I certainly didn’t expect to find you in here, Faenon,” Raz said cheerfully. “Since I know you’re not particularly busy right now, could you help me out with something?”

Althea’s talent for healing came with the usual perks that mages enjoyed: their awareness of all magical energy, including the auras of other people. She rarely found her sixth sense of much use; she once told Faenon that her perception was about as accurate and constrained as her eyesight. She saw Raz approach in her mind’s eye before Faenon saw him with his own eyes only because of the door that stood between them.

Raz extended his papers, bound in a stack with twine, to Faenon with his usual grin: wide, but false. His face was the kind that was just pretty enough to hate. When he winked, which was often, it felt as though he was flaunting his jade-green irises with one eye and his long, dark lashes with his other.

“Would you be a dear and deliver these to the choir for me?” he asked. “They’re copies of sheet music. The music teacher wants them by the end of the day. You know where the choir rehearses, don’t you?”

Faenon had even less of an idea of how to find the choir than the library, but Althea’s persuasion still hung over his shoulders, making his hands open and close to accept the stack of neatly-inked copies.

“I’ll show you where it is. Come on, darling.” Raz gave him a nudge on the back and led the way through the tall summer grasses.

Faenon squirmed away from Raz’s hand and stopped short; he liked being touched by Raz about as much as he liked being called darling. “Why am I going with you if you’re just gonna walk the whole way there, anyway?” he demanded.

Raz laughed like a rich woman: high, melodic, and sophisticated, but diabolical. “I’m pleasantly surprised to find the entire student body doesn’t know yet,” he replied, spinning on the ball of his foot to shoot a smile back at Faenon as he walked ahead. “Don’t worry your pretty little head about it.”

The bell of the clock tower tolled twice. Two o’clock was the end of the last academic class of the day. Faenon glanced uneasily at Raz, who slid a lidded gaze and a knowing smile back.

“Well, I know you’re not going to practice,” Faenon muttered.

Raz had never attended a weapons class in all of his time in Azier. His twin cousins, on their designated days, practiced magic after school in the field along with the few other mages in the town, including Rune. At their young age, they only practiced three out of five days of the week, unlike older students who were permitted to practice weaponry or magic every day. On off days, students could study in the library, head home early, or participate in extracurricular activities such as the choir. According to a credible source, Raz chose to always attend choir rehearsal.

“And you’re not going to practice, either, are you?” Raz replied. “Kari mentioned over lunch that you’ll be having one of your fun family gatherings after school today, so you’ll want to be rested. Not to mention, you’re not as interested in school practices now that Althea’s father has retired from teaching, isn’t that right?”

Faenon’s credible source was evidently a credible source to multiple people. He responded with only a grimace.

The school grounds began to fill with the noise of children, then with their animated bodies, flying in all of the different directions students were liable to go at this hour. Faenon fell back from Raz to avoid a visual association between them. With a stroke of fascination, he watched the students coming towards him. Their faces would twitch towards a scowl as they passed Raz, and then they brightened with a smile once they saw Faenon.

“Hey!” said an unfamiliar boy no older than twelve, a sheathed sword bouncing against his back as he dashed to Faenon’s side. “That was really cool, when you made that guy Mr. Eller talk about the half-elf genocide! You’ll come back, right?”

Raz had been the one to bring up the half-elf genocide, but no one liked Raz. They hated the way he spoke, the color of his hair, his disrespect for the warrior’s way. Faenon gave a flat, one-word reply of some kind to the boy he had never met. In a blink, he was gone again.

Though Faenon stood a head taller than most of the crowd by virtue of his age, he still missed it until the shock of red hair was right under his nose when his brother marched up to him. He clutched the notebook Faenon had left behind in the classroom. He shoved an opened page in Faenon’s face for just long enough that Faenon could read the message scrawled in heavy-handed charcoal: Don’t ever talk in that class again.

“That was—I’m fighting for—for rights, Rune,” Faenon shot back, glancing uneasily at the throng of students who filed past but stole wide-eyed glimpses of the scene unfolding in the middle of the school grounds.

For someone who hated being the center of attention, Rune had a flair for the dramatic. He ripped the page out of the notebook. As he held it half-crumpled in his shaking fist, emerald-green flames burst to life at the edges of the paper, consuming the message in a sudden inferno the color of his eyes. After dropping the smoldering scrap to the ground, Rune shut the notebook. With tiny, precise applications of his fire magic, he seared the words I HATE YOU into the bark of the cover, thrust it into Faenon’s chest, and bolted.

“Wow, your brother’s really getting good with his magic,” Raz chirped.

“Shut up,” Faenon grumbled, staring at the new face of his only notebook.

“Hey, don’t worry. He still coordinates off days with Kari even though she’s not trying magic anymore, and she’s off today,” Raz said. “He’s probably headed home. Your dad can handle him.”

Faenon wrinkled his nose. “How much does Kari tell you about us?”

“Oh, you know how she is. This building, darling.”

Kari was quite a small girl for her age, especially among the bulky builds of Azierites, and her age was only a humble thirteen years. Every word, every action, every gesture she made was in deference, which was why she could say she didn’t mind living with her cousin, as overbearing as Althea could be. She had grown into a sweet, modest girl, the kind one would expect to find sitting in the front row of a group of sopranos when Faenon barged awkwardly into the choir assembly. She stared at him with wide, baby-blue eyes upon seeing something so drastically out of place.

The choir teacher had a name that Faenon vaguely knew, but could not spell or even pronounce. He was a Fiallan man—tall and lean, dark-skinned, with long, straight, black hair in a low ponytail—and his Fiallan name was among the trickiest on Plainsmen’s tongues. Faenon spotted his name written on the board, twice, once as the full Mr. Krystallathisson and once as the simplified Mr. K. The music teacher had not often crossed paths with Faenon, but knew enough to know that the sight of him in the music room was cause for alarm.

Faenon looked over his shoulder for Raz to explain, but found that the boy had disappeared. He shrugged and said, “Copies,” as he held them out.

Mr. K hesitated to accept them. “Who made these?” he asked with the precise consonants and cadence of his accent, though it was faint after years spent away from Fiall.

“I dunno, I guess Raz,” Faenon said with another shrug. “He told me to bring ’em here, then he…”

“I can see that Raz was involved,” Mr. K muttered.

It was only then, after following Mr. K’s eyes, that Faenon noticed the scrap of paper on top of the stack, tucked under the twine that bound the papers in a stack. On it was a short note, the end of which read, Lots of love, sweet pea! –Raz.

In visceral disgust, Faenon almost dropped the ream, fortunately at the same time that Mr. K took hold of it. Mr. K slid the note out from under the twine, balled it in his fist, and did not drop it, but threw it downwards into the waste bin he walked past. Faenon backed out of the room slowly. Kari had nothing but a blank stare for him when he glanced her way.

Raz’s silhouette, backlit by the wide window beside the building entrance, awaited Faenon a short distance down the hall. “He didn’t like your note,” Faenon called blandly.

The light caught on Raz’s teeth when he smiled. “Excellent,” he replied. “That was to spite him.”

Faenon shook his head, disgusted and confused and something else. “The hell is this about?”

“Goodness, Faenon, where have you been all summer?” Raz sighed. “Living under a rock?”

“Living outside of Azier, if that makes a difference,” he said. “Dealing with my brother getting angrier and better at magic at the same time.”

“Has he learned any new tricks? Other than how to put some wood-burning artists out of a job, I caught that one. Very nice.”

“He can pick locks now. It’s the levitation stuff, but smaller. Just pushes the lock like a key would, and he’s in.”

Raz’s eyes flashed. His smile looked empty. “What is that levitation magic he has?” he asked with an inflated lilt to his voice. “I’ve never seen anything like it.”

As they exited the old building, Faenon maintained a greater distance away from Raz. “You’re asking the wrong guy,” he said. “I don’t know jack about magic.”

“I’m just saying he should be a little more careful about who sees him using something so… unique, like that,” Raz warned. “Incidentally! Tell him to drop out of the Human-Elven Relations class.”

Faenon stopped walking midstride, because every muscle in his body went rigid. A chill ran from his hands to his shoulders, then all the way down his spine.

“What the hell did Kari tell you?” he demanded, his voice shaking.

“Nothing I couldn’t figure out on my own, dearie,” replied Raz. “I’m sharper about these things than most people. I’m more experienced.”

Faenon kneaded his fingers into his palms as he balled his hands into trembling fists. He thought about the time Althea told him that a bad head injury could erase someone’s memories. His eyes flicked from side to side, waiting for the closest students to turn all of their backs before he would strike.

“Problem is, a researcher from Meryville University? He’s just as experienced as me,” Raz said, folding his hands behind his head as he gave an easy smile. “So Rune needs to get out of his class. Honestly, the farther he gets from the drivel this guy’s selling as science, the better.”

Faenon’s shoulders sank. His fingers uncurled. “Are,” he asked weakly, “are you on my side, or…?”

“Goodness, Faenon, you’re so dense, I’m worried I’ll pass an event horizon if I get too close to you!” Raz chortled. “Of course I’m on your side.”

“But you—you were on his side back in class! You cheered him on when he made fun of me!”

“That’s because, unlike you, I have to be careful with my opinions if there’s someone I’ve got to protect.”

Despite that worry about being near each other, which Faenon had not understood, Raz clapped both hands onto Faenon’s shoulders. His playful air had faded into a stern gaze.

“So here’s what you have to do,” he said. “You tell Rune to get out of there. You stay, and you fight that man on every piece of garbage that comes out of his mouth. Please.”

Faenon blinked, but his eyes were not betraying him. Raz’s lower lip was trembling with intensity.

“I’m leaving town tonight, for… a while, probably,” Raz added, his hands sliding off of Faenon’s shoulders. “Someone has to keep fighting him, and—and you’re better at it than I am, anyway. You know that.”

“Wait, where are you going?” Faenon demanded. “Why is—?”

“Gonna go live in a treehouse. Me and the twins. Ask Kari, I already told her,” Raz said quickly. “Here, make some kind of one-liner out of this, okay? His name’s Eller, so he’s from that Eller family where none of the boys can be warriors because of some kind of blood problem. So if half-elves are outlawed because of a higher incidence of genetic disorders, then his parents should be arrested for irresponsibly giving birth to him. Make it snappy, somehow. That’s your talent.”

A laugh lifted Faenon’s shoulders. His mind wrapped around the fodder for attack. “I’m gonna destroy him,” he said. “It’s Althea running detention now, anyway. She’s gonna kick my ass every day no matter what. Might as well give her a reason.”

Raz beamed. For once, his eyes were bright and warm.

School ended after practice. Usually Althea and Faenon did not walk home together, since Faenon lived just outside the village gates while Althea was well within them. According to his father’s etymological theories, the town of Azier derived its name from the word axis, or some common root in an older form of the language. The meaning fit in two senses: one, for its precarious position on the world map, and two, for the two cobblestone roads that crossed through the center of the village, spanning the distance from one gate to the other. The North Road eased into a gentle incline as it sloped up towards the start of the Fiallan mountains, and the West Road’s eastern end had fallen into disrepair since before Faenon could remember. Althea once joked that the roads were named after the direction of the country that Azier preferred. To the south, opposite the friendly traders of Fiall, were the barren woods that marked the edge of the lawless Highlands, to the west were the idyllic Northern Plains, and to the east was, of course, Gardena.

On practice days, Althea and Faenon could walk together through the southern gate. Just before the woods, Faenon’s father’s farm had an abandoned pasture outside of a lifeless barn. There had once been animals there, even as recently as Faenon’s earlier memories, but when he remembered the animals, he remembered his mother. He later reasoned that his father had sold the livestock so that he had the time to raise two motherless sons. The fenced-in pasture now served as a battlefield. The barn was where Faenon kept his axe.

Between the rows of vegetation, Corona Winter stood strong under the pressure of the sun. An autumn chill had already returned to the air, preparing for the Northern Plains’ long winter, but the heat of the summer still reigned every afternoon. Corona removed his gardening gloves, wiped the sweat from his hands on his well-worn trousers, and ran his sleeve across his forehead. As he rested, his and Faenon’s eyes met, and they nodded at each other from a distance. His father, like his brother, liked to have time to himself, and the field was their place of solitude.

Althea did not talk to her father, either, but for her own reasons. Deric was a fair-haired man with silver spreading from his temples. Having come from a smithing family, he learned to wield a sword at a young age but, like Faenon, found he preferred the axe. Moriel, whom Althea most resembled, was a thoroughbred Azierite, meaning she was noticeably larger than her husband. She was skilled at using all types of swords and gave Deric expert advice on their design. Both used to teach classes at the school, Moriel only when demand was high. Deric, once the primary teacher for the axe, grew older as Faenon grew stronger under his tutelage. The previous school year had been his last.

Ever since Faenon received his first dummy axe, made of wood with a dulled edge, the two families had come together to battle in the pasture. The practice benefited both Faenon, who had zeal for this civilized violence from a young age, and Althea, who could only learn to heal from a steady stream of mild injuries. The wounds became more serious and more complicated as she became more skilled, as Faenon learned to wield a true axe forged for his hands by Deric, as Rune began to learn magic, as Kari joined in with her bow and arrows, and as the battles became less like play and more like reality.

Althea sat by the barn door and Corona stood over her. Faenon, Rune, and Kari faced Deric and Moriel in the golden grass. They arranged themselves not for one battle but two separate ones; Deric was unofficially Faenon’s opponent alone. Deric recognized every mistake that Faenon made and could take advantage of each one. His criticism was unforgiving, but he usually coupled it with kind laughter as he helped Faenon to Althea’s side after a nasty hit and a lesson learned.

Faenon knew from a glance that today he would not be so kind. Deric’s expression was not unfamiliar, but when such fatigue lined his face, his dark eyes usually sought out Althea from time to time, so that Faenon could take advantage of his distractedness to triumph. Today, Deric stared him down, unblinking, and his axe was brutal. Faenon fell to his knees before the aging man more times than he could count on his blistering fingers, and Deric had no smile or word of advice. Once, he murmured, “You’ve got to get better than this.”

Corona disappeared into the house during the fight, and when it stopped not at Althea’s call of exhaustion, but Faenon’s, a simple but plentiful dinner was ready, filling the house with the hearty aroma of vegetables that had come into season. Instead of discussing Faenon’s performance in the battle, Deric remained withdrawn, twirling a spoon on the bottom of his bowl of soup. When he lifted his eyes, they fell not on Althea, but on Corona.

The Riders did not linger after dinner. As Faenon scrubbed dishes clean for his brother to rinse and dry, Corona tapped his shoulder and said, “Althea tells me you’ve already made a good impression on one of your teachers.”

Faenon slammed a stone bowl to the table and rolled his eyes. “He was being a snob,” he protested. “A racist, Gardenian snob.”

“Gardenians are people, too, Faenon,” Corona chided gently. In a village full of simple-minded men easily incensed to rash action, he valued reflection and empathy.

“He was going on and on about how half-elves are these tragic creatures born with defects,” Faenon complained, ignoring his brother as he set down dishes with shaking hands and left the room without a word. “And then he just kept talking down to me and telling me it was stuff I wouldn’t understand when he didn’t even try to explain it. He had absolutely zero respect for me.”

“Of course he had no respect for you, Faenon,” Corona said, watching Rune’s bedroom door close. “Did you give him a reason to respect you?”

Faenon opened his mouth to say something, but felt his cheeks flush when he found no words.

“You always complain about not being respected by adults, but you forget that you will have to earn your elders’ respect,” Corona said. “You should consider that an advantage, that they expect nothing from you and you can impress them to earn their respect. It is a far worse thing to be afforded respect as a courtesy and have it revoked when you don’t meet expectations. See to it that you keep both of these lessons in mind.”

Faenon’s blood boiled, but he was in the habit of keeping lessons from his father in his mind. “I’m angry because I know you’re right, and I don’t want to talk about it right now,” he said through gritted teeth.

“That’s fair. Thank you, Faenon,” said Corona with a smile. “Can we still talk if I change the subject?”

“Depends.”

“How is Rune?”

Faenon sighed and leaned on the counter under the renewed weight on his shoulders. “He’s brilliant. He needs to go to University someday. You know he does,” he said. “But it’s getting worse at school.”

“And Kari wasn’t able to help?” said Corona.

“They’re not in any of the same classes anymore. Probably for the best,” Faenon muttered. “The way he is, I feel like he’s gonna start lashing out at her next. Not just me anymore.”

Corona rested a heavy hand on Faenon’s back. “Some days I wonder what I did to deserve such a troublesome son,” he confessed, “and then there are days like today, when I wonder what I did to deserve the perfect one.”

Faenon shivered. “Hey, give me some warning before you say weird stuff like that,” he mumbled.

“Sorry,” said Corona. “I just know we’ll be parting ways soon.”

Through years of chopping firewood and hunting in the outskirts of the forest that bled into the wild Highlands, Faenon had earned petty change that he collected in a box under his dresser. He had hidden the box to keep it from his father, back when he was afraid to say that he did not want to stay on the farm. Hiding the box could not hide the dream; Corona saw the desire to leave Azier in his son’s eyes. He told the story of his two brothers, who, as young men, left Azier, which he called a toxic place. He explained that he would never want to hurt his children by chaining them to a place in which they could not thrive, but just the same, he would never want to hurt his children by not teaching them everything they could possibly know before he let them go. So Corona agreed to support Faenon in any choice he made, on the condition that he completed his education. Faenon kept the box under his dresser in case he could not wait that long.